American Game, Booted Bantam, Campine, Frizzle, Leghorn, Orloff—the chicken is yoked to one of the most famous philosophical questions: Which came first, the chicken or the egg? This conundrum dates back to Aristotle who puzzled, “there could not have been a first egg to give a beginning to birds, or there should have been a first bird which gave a beginning to eggs; for a bird comes from an egg.” Since Aristotle’s time, thinkers such as Hegel and Marx have opted for a less causal, more dialectical answer in order to understand the chicken-egg relationship, and science tells us the egg evolved long before the bird. In “How the Chicken Conquered the World,” Jerry Adler and Andrew Lawler write, “In contemporary American usage, the associations of “chicken” are with cowardice, neurotic anxiety (“The sky is falling!”) and ineffectual panic (“running around like a chicken without a head”).” Aside from morally instructive children's stories like Henny Penny (commonly known as Chicken Little), television shows ranging from I Love Lucy to Arrested Development have played upon these usages for comedic purposes. Of course, the chicken plays a more literal and serious role in today’s world. The blood sport of cockfighting, for instance, illustrates the ferocity of the males who are bred, trained, and armed with “metal spurs and small knives strapped to the bird’s leg.” While cockfighting is illegal in the United States, it’s still practiced in various parts of the world, and practitioners boast its long lineage. And let us not forget the chicken feeds us. Baked, barbecued, or fried, in the U.S. alone, close to 8 billion chickens are consumed each year, and approximately 50 billion eggs are produced. We are faced with a new philosophical consideration, one said best by Seinfeld character George Costanza: “You think chickens have individual personalities? If you had five chickens, could you tell them apart just by the way they acted? Or would they all just be walking around ‘bak bak baak bak?’ Because if they have individual personalities, I'm not sure we should be eating them.”

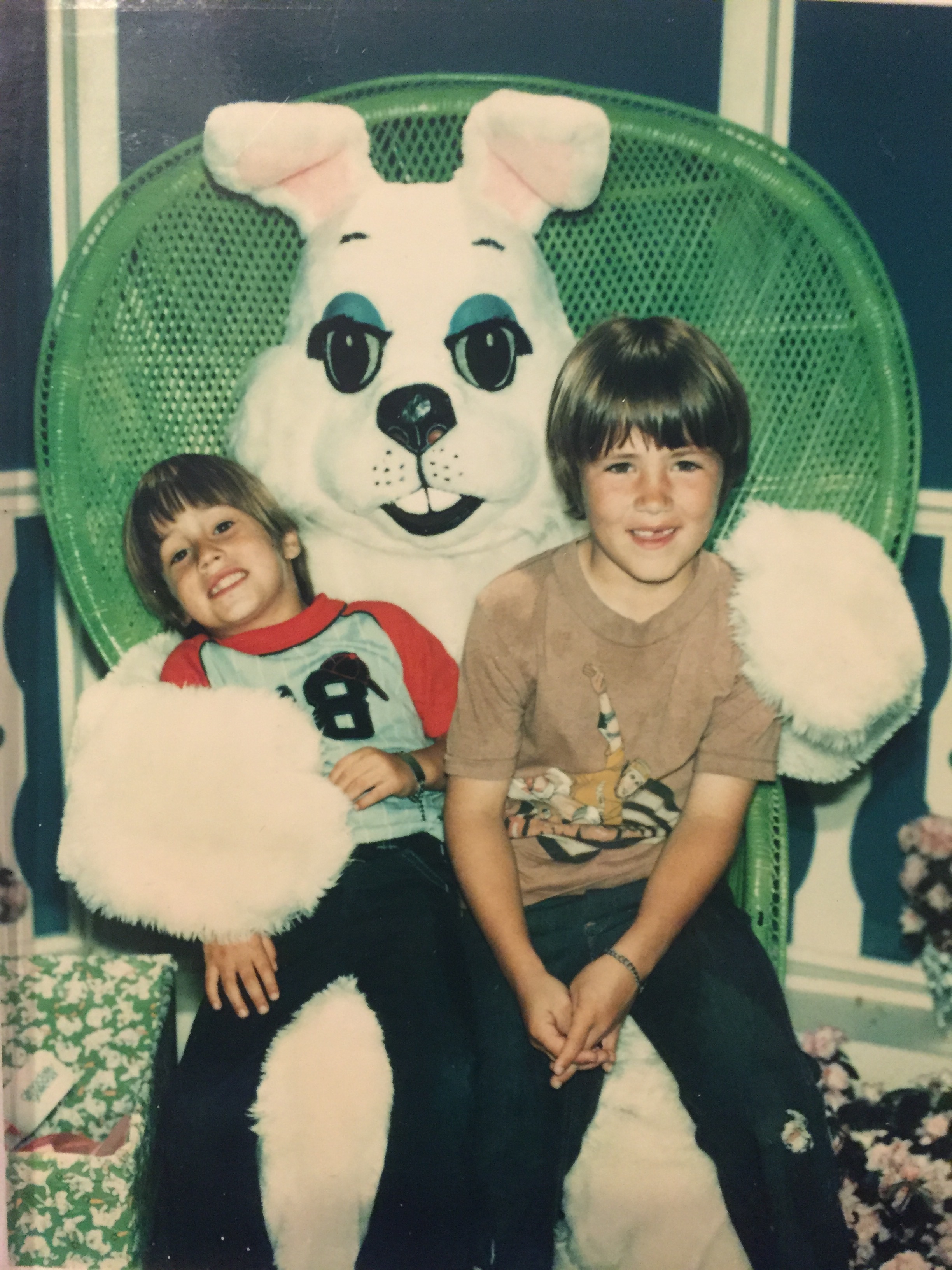

Happy Easter

The Easter Bunny and Easter eggs are the result of an unfortunately clumsy hybrid of pre-Christian mythology with Protestant Germanic culture. Easter, like Christmas, Mardi Gras, Valentine’s Day, and Lent itself, are modern versions of fertility festivals that date back to the discovery of agriculture and the domestication of animals in Neolithic times. Rabbits and hares have always been symbols of sexuality for their prodigious reproductive powers. In various mythological systems, eggs are signifiers of both fertility and rebirth, and appear in various creation myths. Given the primordial linkage between Spring as the conjunction of sexuality/fertility and purity/rebirth, the conflation of rabbits and eggs, strange as it may seem biologically, makes perfect sense mythologically. In antiquity hares were actually considered a hermaphrodite-type animal with the power of parthenogenesis (asexual reproduction). The celebration of Jesus’ Resurrection fits into the structure of Spring festivals and thus assimilates pre-Christian symbolism but it is important to note that the Easter Bunny is a particularly Protestant amalgamation of pagan mythology in Germanic and Anglo-American culture. Most Christian cultures name the holyday from the Hebrew word for Passover as it was translated to Aramaic, Greek and Latin and into modern languages (e.g., French Pâques, Italian Pasqua, Spanish Pascua). David Sedaris shows us the difficulty of explaining this most strange of “Christian” symbols in his essay “Jesus Shaves.” Happy Easter!

Spiders Trust in Airy Dreams

In Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Arachne weaves a narrative in a tapestry so exquisite that Athena, green with jealousy, turns her into a spider. Since this ancient tale was spun, the spider has graced the pages of countless texts and is often described as the opposition to orthodoxy, most notably in Swift’s “The Battle of the Books.” Cast as the modern quarreler in the debate against the ancients, the spider is criticized for threading its mansion from the entrails of its own guts (the blood of other insects). But before Aesop arrives at this judgement, he attests: “For, pray, gentlemen, was ever anything so modern as the spider in his air, his turns and his paradoxes? He argues on the behalf of you his brethren and himself, with many boastings of his native stock and great genius; that he spins and spits wholly from himself, and scorns to own any obligation or assistance from without. Then he displays to you great skill in architecture, and improvement in the mathematics.” In this light, it is easy to see why the spider still inspires modern writers. In his poem “The Spider,” Loren Eiseley takes up the the spider's case and describes him as the master of architecture who knows not to build a foundation where it can be “forfeit to the mole and worm.”

The Spider

By Loren Eiseley

His science has progressed past stone,

His strange and dark geometrics,

Impossible to flesh and bone,

Revive upon the passing breeze

The house the blundering foot destroys.

Indifferent to what is lost

He trusts the wind and yet employs

The jeweled stability of frost.

Foundations buried underfoot

Are forfeit to the mole and worm

But spiders know it and will put

Their trust in airy dreams more firm

Than any rock and raise from dew

Frail stairs the careless wind blows through.

The Naming of Cats

Over 4000 years ago the Ancient Egyptians domesticated and revered cats for their expert hunting skills and their practical ability to keep rats and other nuisance animals at bay. Of course, some people, such as George F. Will, declare: “The phrase ‘domestic cat’ is an oxymoron.” For, who can really own (or truly know) a cat? T.S. Eliot’s poem “The Naming of Cats” reminds us the cat has three names—the “sensible” name he is called by familiars, the knowable yet unique name that “never belong[s] to more than one cat,” and “The name that no human research can discover— / But the cat himself knows, and will never confess.” While the Ancient Egyptians worshiped these mysterious creatures as gods and goddesses, we worship them as entertainers. The musical Cats, inspired by Eliot's Old Possum's Book of Practical Cats, premiered on Broadway in 1982 and drew audiences for nearly twenty years. Today, the Internet abounds with cat videos gone viral. This genre has even demanded recognition through the establishment of the Internet Cat Video Festival. Perhaps our contemporary fascination with these carnivorous, agile felines springs from our untamable desire to know more about our own domesticity, to know our own unnameable Name.

The Naming of Cats

by T.S. Eliot

The Naming of Cats is a difficult matter,

It isn’t just one of your holiday games;

You may think at first I’m as mad as a hatter

When I tell you, a cat must have THREE DIFFERENT NAMES.

First of all, there’s the name that the family use daily,

Such as Peter, Augustus, Alonzo, or James,

Such as Victor or Jonathan, George or Bill Bailey —

All of them sensible everyday names.

There are fancier names if you think they sound sweeter,

Some for the gentlemen, some for the dames:

Such as Plato, Admetus, Electra, Demeter —

But all of them sensible everyday names.

But I tell you, a cat needs a name that’s particular,

A name that’s peculiar, and more dignified,

Else how can he keep up his tail perpendicular,

Or spread out his whiskers, or cherish his pride?

Of names of this kind, I can give you a quorum,

Such as Munkstrap, Quaxo, or Coricopat,

Such as Bombalurina, or else Jellylorum —

Names that never belong to more than one cat.

But above and beyond there’s still one name left over,

And that is the name that you never will guess;

The name that no human research can discover —

But THE CAT HIMSELF KNOWS, and will never confess.

When you notice a cat in profound meditation,

The reason, I tell you, is always the same:

His mind is engaged in a rapt contemplation

Of the thought, of the thought, of the thought of his name:

His ineffable effable

Effanineffable

Deep and inscrutable singular Name.